New Yorkers have been taking the plunge in the Big Apple since the late 1800s, when the state legislature passed a law mandating free bathhouses in cities with populations over 50,000.

The state believed it was necessary to provide bathing facilities for families in overcrowded tenements, where sanitary issues were a major concern.

Bathhouses, the predecessor of the swimming pool, were initially used for cleansing and therapeutic purposes but became more geared towards recreation over the years.

Along with bathhouses, New York City also boasted “floating baths,” along both the East and Hudson Rivers. These wooden baths were filled with river water and secured by pontoons, boasting dressing rooms for men and women.

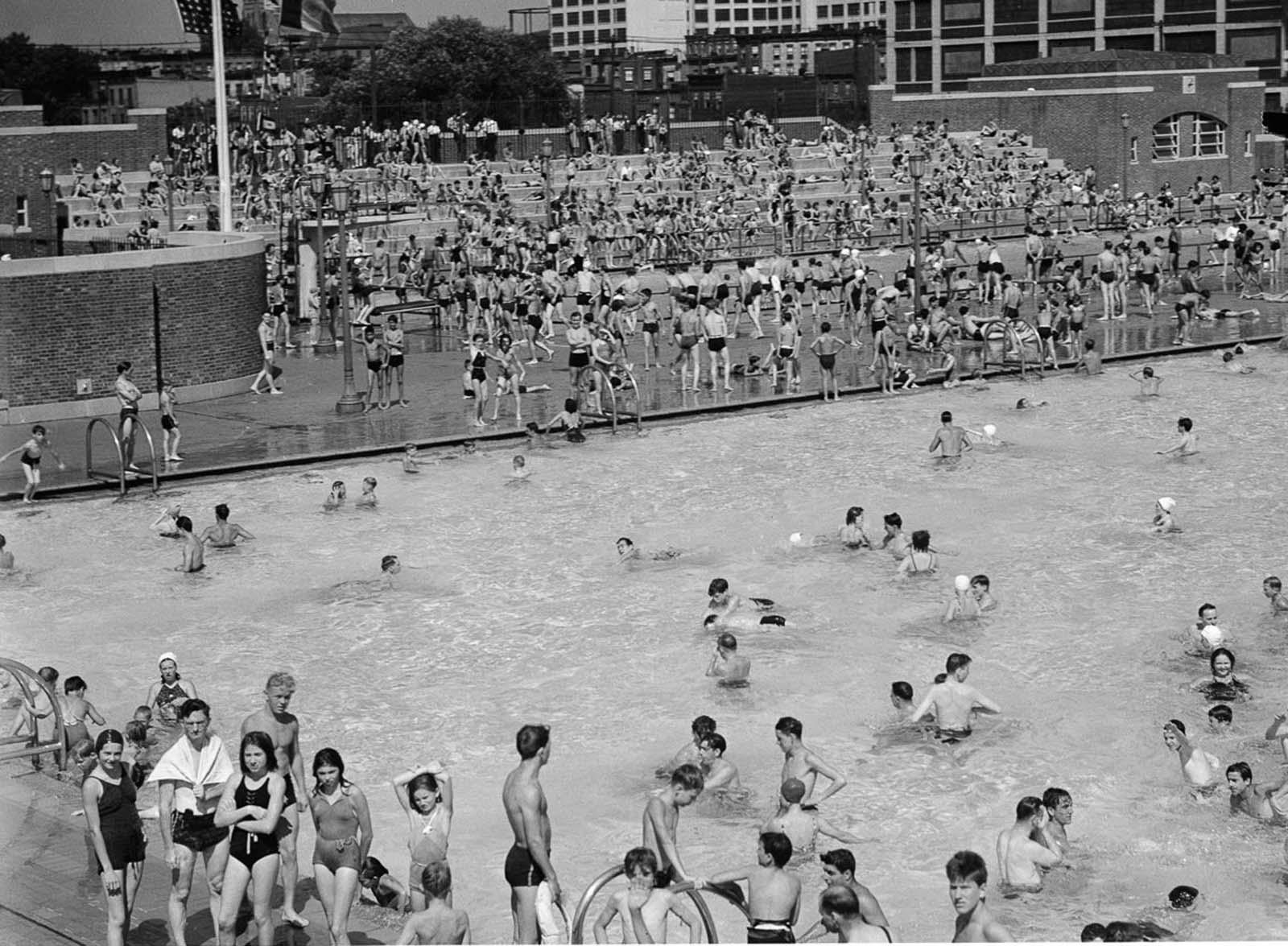

Astoria Park Pool, 1936.

However, these scenic watering holes were short-lived because of the increased concern of river pollution and the limited number of seasons they could be in use.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Parks Department became the authority of bathhouses and in conjunction with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) began a large-scale project to create several grand bathhouses and outdoor pool complexes.

Faber Park Pool, 1938.

NYC’s swimming pools were among the most remarkable public recreational facilities in the country, representing the forefront of design and technology in advanced filtration and chlorination systems.

The influence of the pools extended throughout entire communities, attracting aspiring athletes and neighborhood children, and changing the way millions of New Yorkers spent their leisure time.

The first eleven pools were opened within weeks of each other in the hot summer of 1936, bringing relief to thousands upon thousands of New Yorkers.

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses attended packed dedication ceremonies that summer.

At Thomas Jefferson Pool, more than 10,000 celebrated the opening, at which the Mayor said, “Here is something you can be proud of. It is the last word in engineering, hygiene, and construction that could be put into a pool.”

Betsy Head Pool, 1940.

The pools were not just huge but also examples of state-of-the-art engineering and fine design. The planning team, led by architect Aymar Embury II and landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke, produced a series of distinct complexes, each one sensitive to its site and topography.

Massive filtration systems, heating units, and even underwater lighting provided a more controlled bathing experience than the often treacherous and polluted waterfront currents in which the city’s masses had traditionally swum.

The palette of building materials was mainly inexpensive brick, concrete, and cast stone, but the styles ranged from Romanesque Revival to Art Deco.

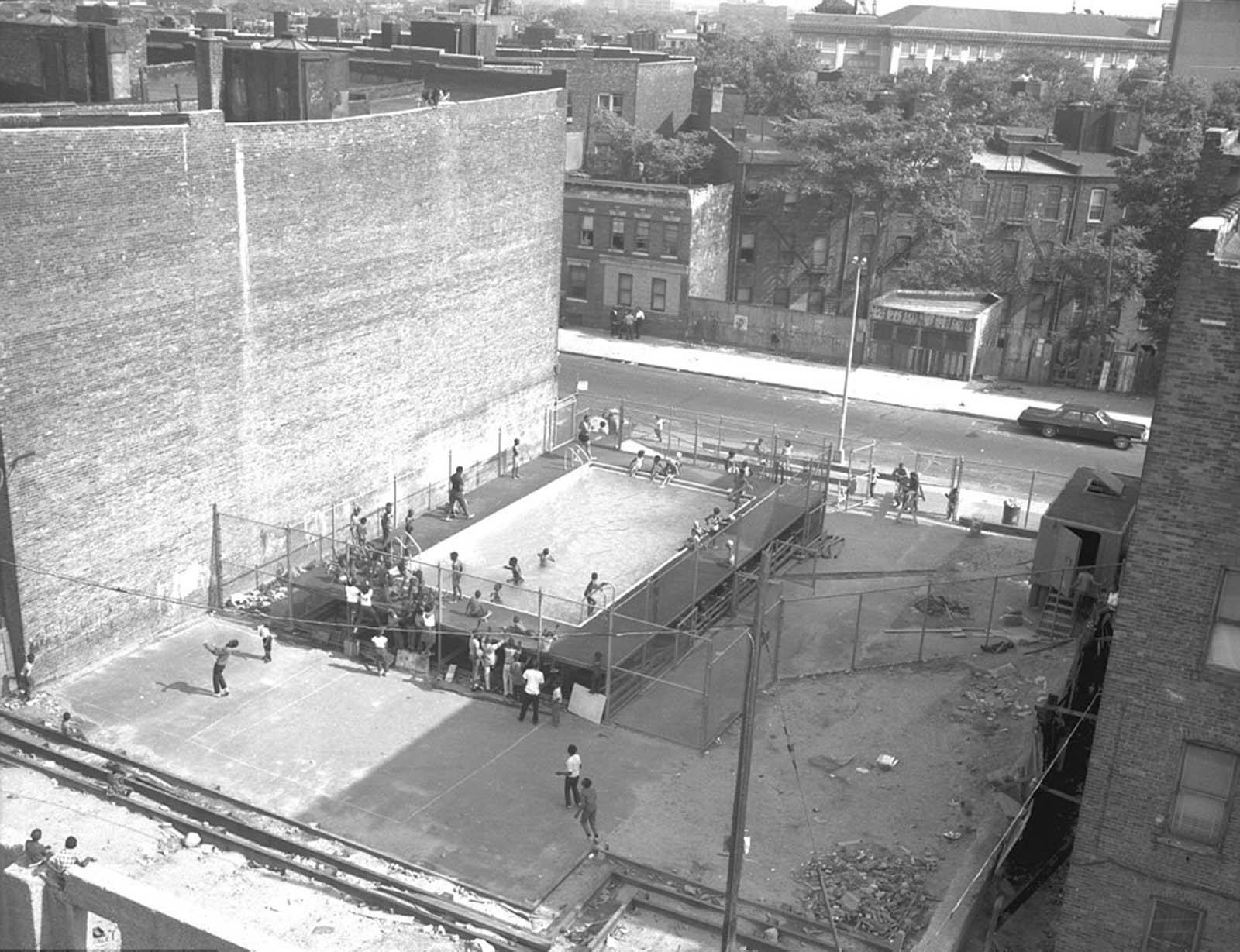

Dozens of children and adults are pictured above crowded in and around what was called a ‘swimmobile’ in the late 1960s.

These WPA pools were designed to adapt to off-season uses such as paddle tennis, shuffleboard, volleyball, basketball, and handball.

Wading pools were used as roller skating rinks, and indoor locker rooms and changing areas were adapted for boxing instruction and evening dance halls for teens.

In 1966, a pilot program created “portable pools” with two pre-engineered, prefabricated 20′ x 40′ aluminum or steel above-ground pools with 6′ wide attached wooden decks.

The average depth of these pools was between 3 and 3.5 feet, and the structures cost approximately $25,000 each.

Red Hook Pool. 1938.

The portable pool program was meant to provide pool facilities to underserved neighborhoods throughout the five boroughs, much the way a portable classroom provides provisional classroom space. These pools were designed to be easily moved as neighborhood needs shifted.

The portable pools were designed for youths 14 and under and over four feet tall and were open from early July to mid-August.

Although each mini-pool was located next to a shower and comfort station, there were no changing areas, and children were to arrive at the site in their swimming suits.

Today many of New York City’s original pools are still in operation and most have received a substantial facelift to accommodate the citizens’ needs for summer activities.

McCarren Park, 1937.

Flushing Meadows-Corona Park Pool, 1946.

Betsy Head Pool, 1946.

McCarren Park Pool, 1937.

McCarren Park Pool, 1937.

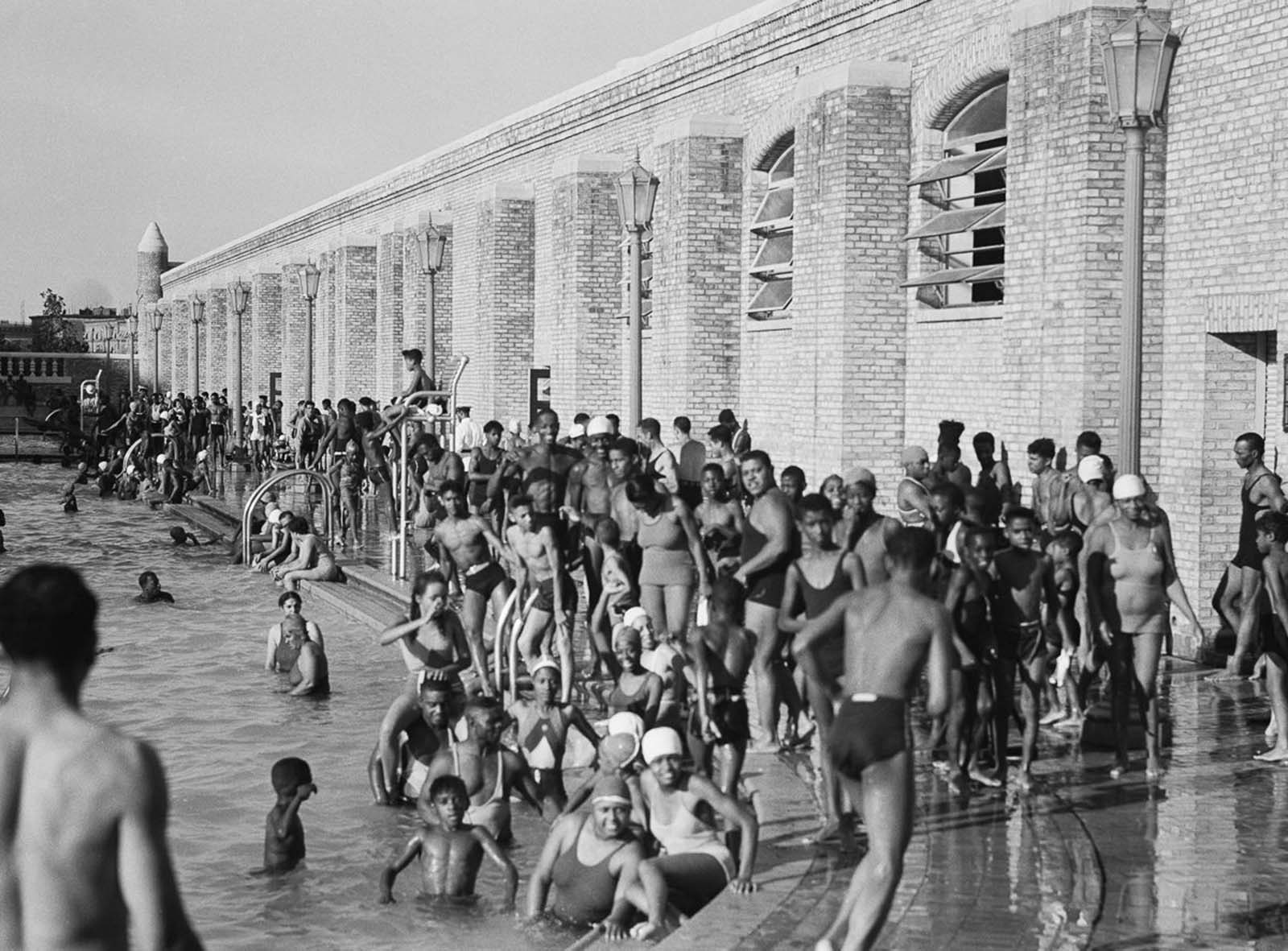

Colonial Park Pool (now Jackie Robinson Park), 1936.

Colonial Park Pool (now Jackie Robinson Park), 1936.

Thomas Jefferson Park Pool, 1936.

Wading pool, Carmansville Playground, 1935.

Swimming contest, Astoria Park Pool, 1936.

A group of young children are pictured above while waiting for the new pool at Thomas Jefferson Park to open on June 27, 1936 in East Harlem, New York.

A young man is pictured above on August 17, 1943, completing an incredible dive during a competition at Astoria pool, which still exists today.

A temporary pool inside the formerly named Tompkins Park in Brooklyn on August 10, 1966. The park is now called Herbert Von King Park.

Besides traditional pools in the city, there were also what were then called floating baths, like the one pictured above at 96th Street on the Upper West Side on August 19th, 1938. The water inside this pool was actually water from the Hudson River.

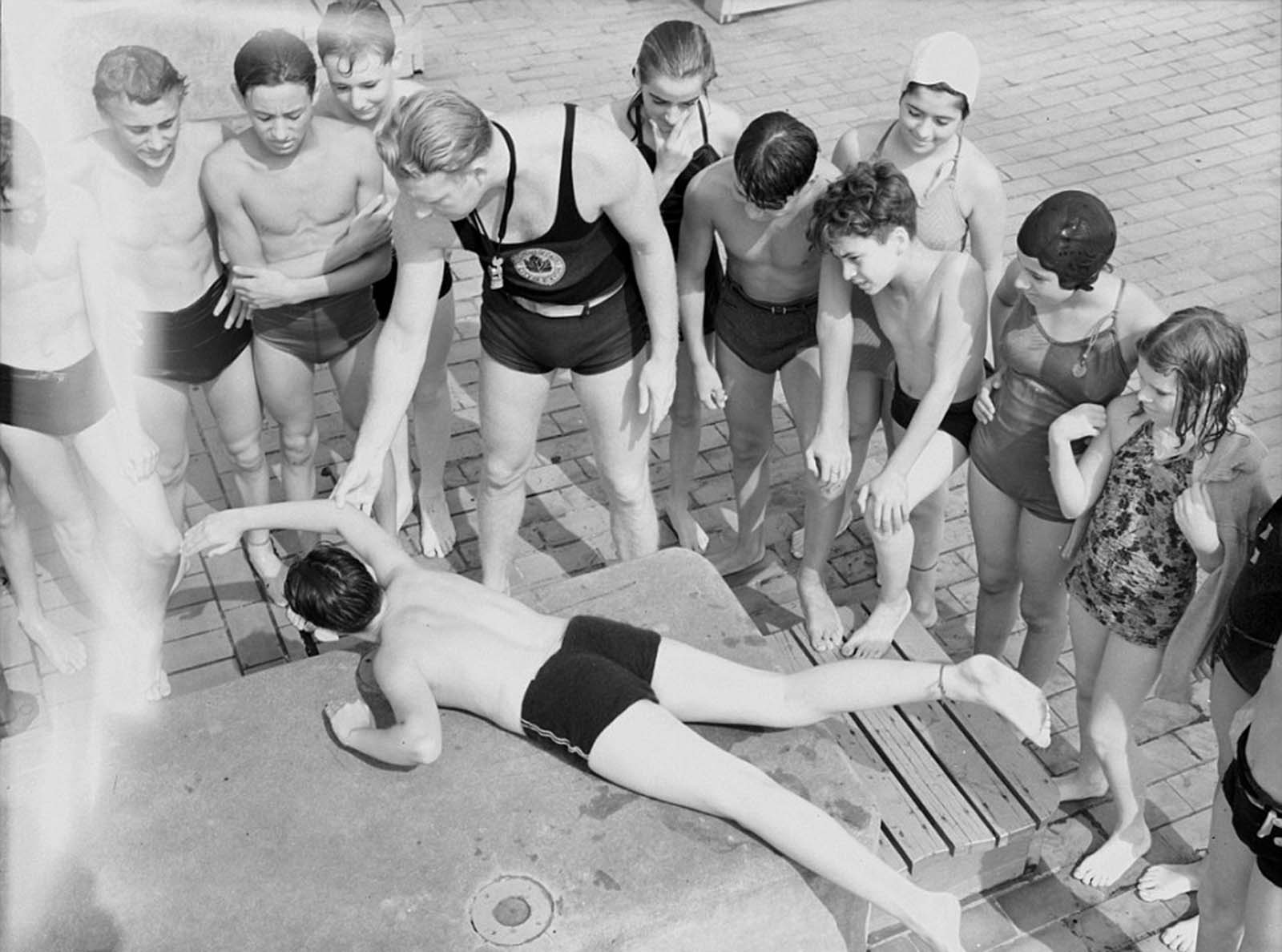

Children are pictured above learning to swim during a class session at the Astoria Pool in 1940. The city offered free swimming lessons to those who swam at the public pools.

A super-crowded McCarren Park pool in Brooklyn during the summer of 1937; the park and pool still exist today.

Dozens of New Yorkers gather around the Astoria pool on August 20, 1936, during a swim competition.

Swimmers taking a dip into a temporary pool at the Stroud Playground in Brooklyn on July 29, 1967.