The racers line up at the starting point in Times Square.

At the dawn of the 20th century, automobiles were an infant technology with none of the infrastructure we take for granted today: road maps, traffic signals, pavement, gas stations, fast food, parking lots, expressways, or motels.

Most people in the world had never seen a car in person. What, then, could be more fun than the first ’round-the-world automobile race under such punishing conditions?

In the summer of 1907, Paris newspaper Le Matin and the New York Times announced “The Great Race: New York to Paris by Automobile”. The prize: a 1,400‐pound trophy and proving that it could be done.

The race commenced in Times Square on February 12, 1908. Six cars representing four nations were at the starting line for what would become a 169-day ordeal (making it, in terms of time taken, still the longest motorsport event ever held).

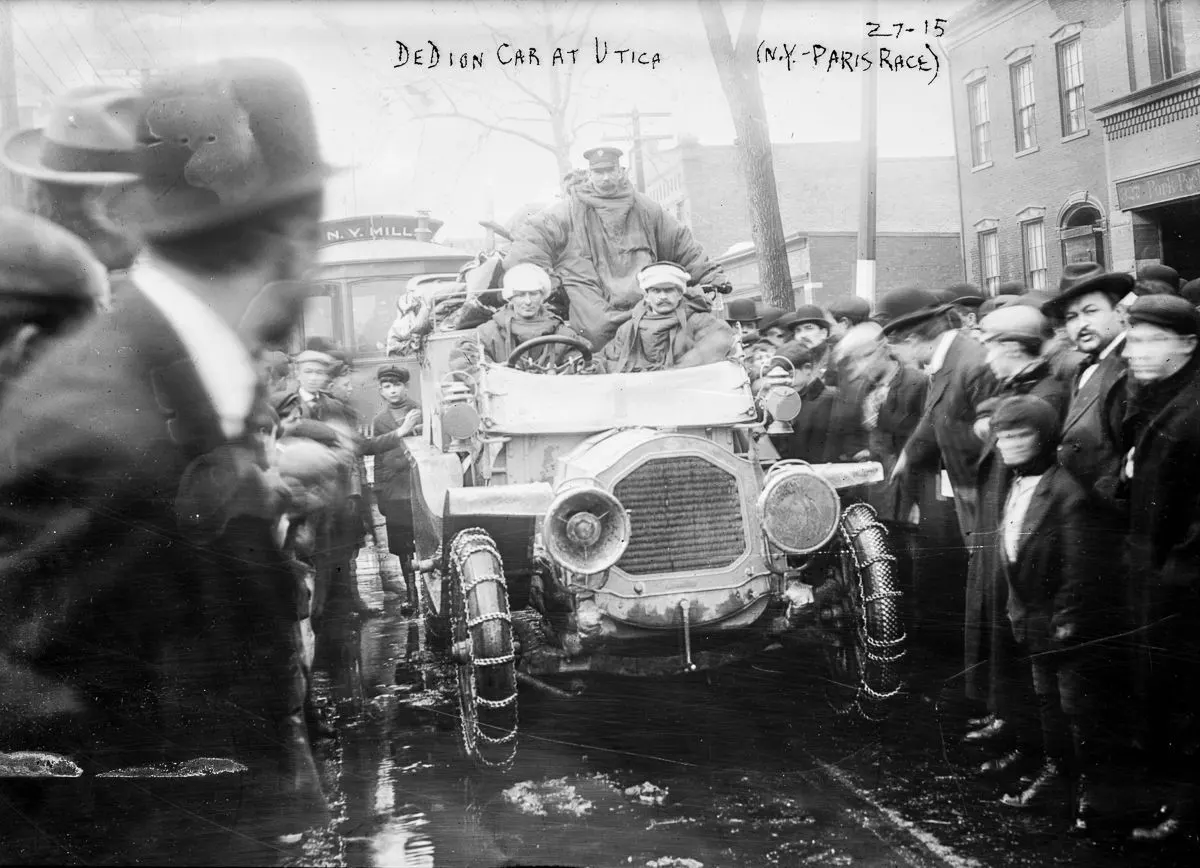

Germany, France, Italy, and the United States participated, with the Protos representing Germany, a Zust representing Italy, three cars (De Dion-Bouton, Motobloc, and Sizaire-Naudin) representing France, and a Thomas Flyer representing the United States.

An enormous crowd fills Times Square to see the racers take off.

Legend has it that the Thomas Flyer entered the race at the insistence of President Theodore Roosevelt, who hated the prospect of European automobiles crossing the country unchallenged by Americans.

Better-established companies, such as Buffalo’s Pierce-Arrow, declined to enter. But the Thomas Automobile Company, also from Buffalo, pulled one of its production models out of its factory at the last minute and entered the race. Buffalo’s own George Schuster was the driver and chief mechanic.

The proposed route was across the United States, through areas with very few improved roads, and then north to Alaska (by boat) and then across the (hopefully frozen Bering Strait into Siberia. Then across Siberia to Moscow and then on to Paris.

The Thomas Flyer reached San Francisco in 41 days, 8 hours, and 15 minutes — the first-ever crossing of the United States by a car in winter.

The car was then shipped up to Seattle and on to Valdez, Alaska. As the Americans turned north, the line of followers stretched from California to Iowa.

The Zust was in Omaha, the De Dion in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the Moto‐Bloc in Maple Park, Illinois, and the Protos a in Geneva, Illinois. Another French car, contending with mechanical problems, was forced to drop out.

The Italian Zust car, with driver Emilio Sirtori and journalist Antonio Scarfoglio.

The Thomas crew found impossible conditions in Alaska and returned to Seattle. The race was rerouted across the Pacific by steamer to Japan where the Americans made their way across to the Sea of Japan.

Then it was on to Vladivostok, Siberia, by ship to begin crossing the continents of Asia and Europe. Only three of the competitors made it past Vladivostok: the Protos (Germany), the Züst (Italian), and the Flyer (American).

The wet plains of Siberia and Manchuria during the spring thaw made progress difficult. At several points, forward movement was often measured in feet rather than miles per hour.

Eventually, the roads improved as Europe approached and the Thomas arrived in Paris on July 30, 1908, to win, having covered approx 16,700 km. The Germans, driven by Hans Koeppen, arrived in Paris four days earlier but had been penalized a total of 30 days for not going to Japan and for shipping the Protos part of the way by railcar.

That gave the win to the Americans with George Schuster (the only American to go the full distance from New York to Paris) by 26 days (still the largest winning margin in any motorsport event ever). The Italians arrived later in September 1908.

The American Thomas Flyer, driven by George Schuster and Montague “Monty” Roberts.

Schuster enjoyed the Flyer’s triumphant return to Times Square on August 17, 1908. After the accolades and parties died down, he returned to his job at the Thomas factory, where he was promised employment as long as the company was in business.

Five years later, the Thomas company collapsed, and all its goods were auctioned off. Lot number 1829 was listed simply as the “Famous New York to Paris Racer.” The winning Thomas Flyer is on display in Reno, Nevada, at the National Automobile Museum, alongside the trophy.

The race was of international interest with daily front page coverage by The New York Times (a cosponsor of the race with the Parisian newspaper Le Matin).

The significance of the event extended far beyond the race itself: it established the reliability of the automobile as a dependable means of transportation. Also, it led to the call for improved roads to be constructed in many parts of the world.

The French Moto-Bloc, driven by Charles Godard.

The Sizaire-Naudin of Pons, Deschamps and Berlhe

The German Protos Car, driven by Lt. Hans Koeppen.

The racers set out from Times Square.

The French De Dion drives through Utica, New York.

Emilio Sirtori drives the Italian Zust through Utica, New York, followed by the American Thomas Flyer.

G. Bourcier de St. Chaffray drives the French De Dion.

Hans Koeppen drives the German Protos through Marshalltown, Pennsylvania.

The German Protos car passes through Grand Island, Nebraska.

Racers pass through Grand Island, Nebraska.

The drivers of the American Thomas Flyer car wait for the ferry in Valdez, Alaska.

The American Thomas Flyer drives through Kobe, Japan.

The American Thomas Flyer car drives through the Manchurian countryside.

The American Thomas Flyer car stops outside an inn in Manchuria.

The American Thomas Flyer car drives through Manchuria.

Crowds gather in Berlin for the arrival of the racers.

Map of the route

(Photo credit: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons / Smithsonian Mag / Buffalo and Erie Country Public Library).