Eero Saarinen’s outlandish air terminal for TWA at New York’s JFK International Airport was sculpted as an abstract symbol of flight. Unlike most air terminals, which seemed intent on depressing passengers, Saarinen’s not only raised the spirits but also showed that concrete structures could be truly delightful.

Saarinen himself described this intriguing building as one “in which the architecture itself would express the drama and excitement of travel…shapes deliberately chosen in order to emphasize an upward-soaring quality of line.”

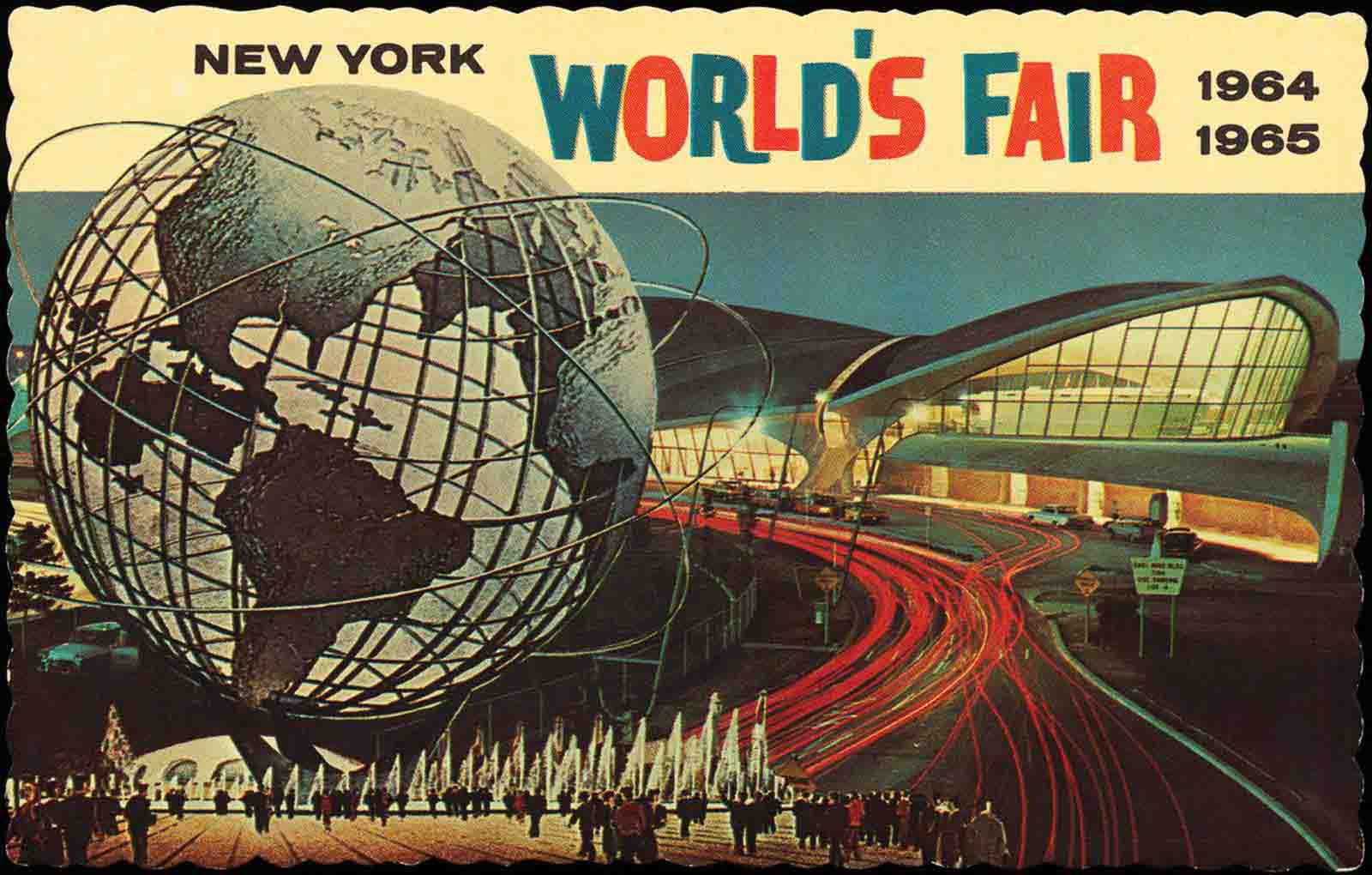

Initially known as the Trans World Flight Center, the TWA Airport Terminal rose as one of several stand-alone terminals that made up the original Idlewild Airport (now JFK International) in Queens, a borough of New York City.

The TWA Terminal, by Eero Saarinen and Associates, became the culminating work in Saarinen’s search for the dynamix sculptural expression in reinforced-concrete constructions. The architect died during emergency neurosurgery in 1961, the year before the terminal building opened.

The commission from the Trans World Airlines Company was made in 1956, just as Saarinen came to worldwide prominence with the completion of the General Motors Technical Center (1955) in Warren, Michigan.

The airline company wanted something much bolder from Saarinen for its New York terminal, expecting that its masterpiece would likewise represent the airline’s status as the industry leader.

The Saarinen team started devising designs for the terminal’s form in February 1956. Although the site assigned to TWA was not the airline’s first choice for an Idlewild terminal, the design team took advantage of the site to design a highly visible terminal.

To model the roof of the TWA terminal, Saarinen’s team created several models made of wire, cardboard, and clay. In addition to around 130 possible plans created by the Saarinen office for the terminal, contractors provided hundreds of their own drawings. Cross-sections and contour maps were also devised. The drawings took some 5,500 man-hours to produce.

Construction began in June 1959, involving 14 engineer and 150 workers. When Eero Saarinen died unexpectedly of a brain tumor in 1961, his associates, principal designer Kevin Roche and John Dinkeloo formed Roche-Dinkeloo, which worked to complete the building.

The TWA featured a prominent wing-shaped thin shell roof supported by four “Y”-shaped piers. The design incorporates elements of the Futurist, Neo-futurist, Googie and Fantastic architectural styles.

The form, or layout, of the TWA Flight Center’s head house is designed to relate to its small wedge-shaped site, with walkways and gates placed at acute angles.

Saarinen described the head house form as being like the “Leonardo da Vinci flying machine”, according to his associate Kevin Roche. Radiating out from the head house are two departure-arrival passenger tubes extending southeast and northeast.

The TWA Flight Center was one of the first to utilize enclosed passenger jetways, which extended from “gate structures” at the end of each tube. In the original plans, aircraft would be available via the “Flight Wing”, a single-story building that passengers would have to walk to at ground level.

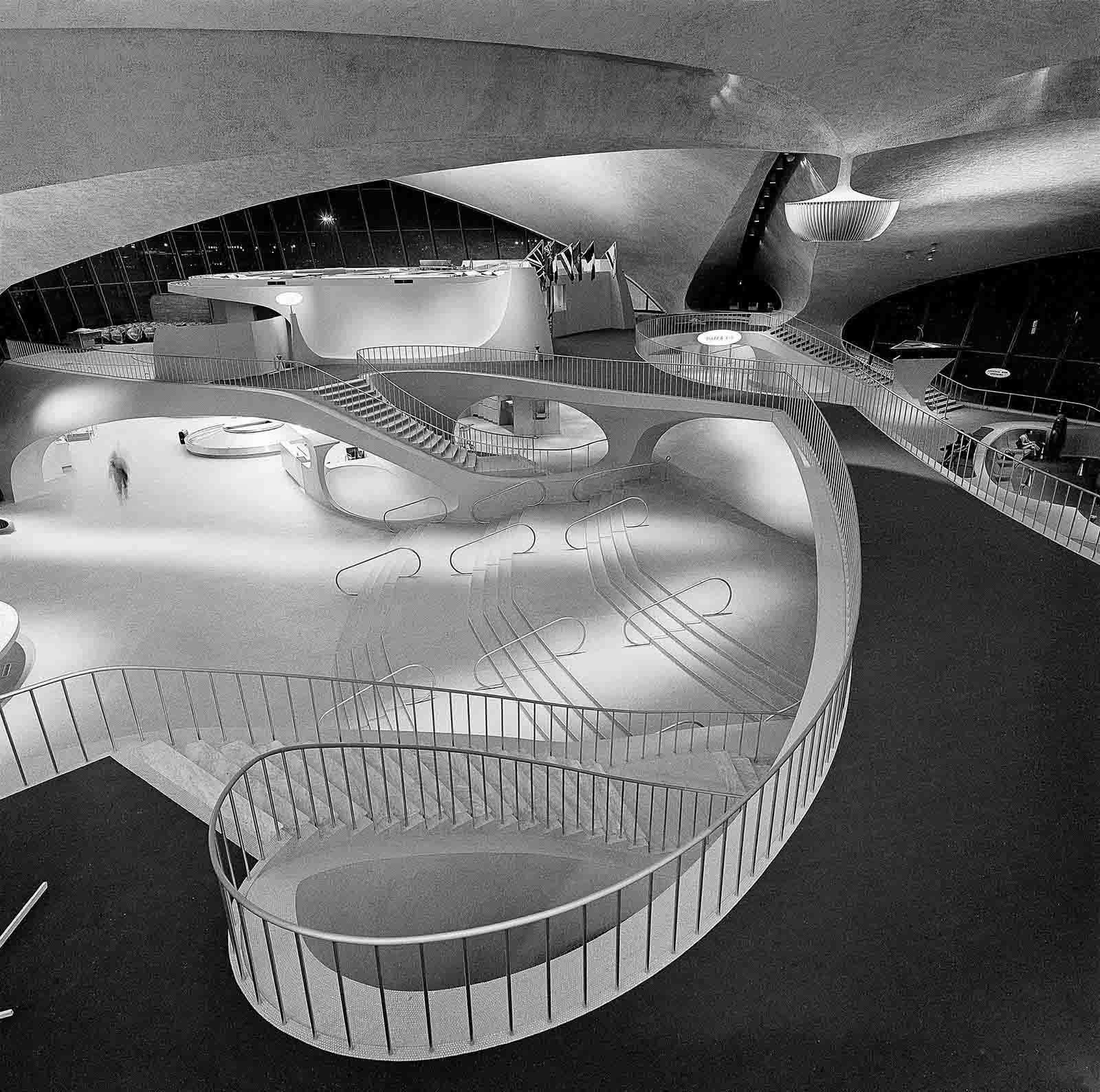

Inside was an open three-level space with tall windows enabling views of departing and arriving jets. Two tube-shaped red-carpeted departure-arrival corridors extended outward from the terminal, connecting to the gates.

The TWA Flight Center incorporated many innovations upon its completion, including closed circuit television, a central public address system, baggage carousels, electromechanical split-flap display schedule board and baggage scales, and the satellite clustering of gates away from the main terminal. The intermediate level contains an area facing east, where passengers could originally see the tarmac.

The ticket counter and baggage claim areas were placed at ground level, on the other side of the curbside canopy, to maximize convenience for passengers. A sculpted marble information desk rose from the floor as a single slab.

A concrete balcony on the upper floor spans the central staircase from the lower floor to the intermediate level. The TWA operated its Ambassador Club on the northern (left) portion of the upper floor.

Three restaurants were located on the southern (right) portion of the upper floor: the Constellation Club, Lisbon Lounge, and Paris Café. Offices were also located on the upper level, north and south of the public areas.

The TWA Flight Center continued to operate as an air terminal until 2001. Its design received much critical acclaim; both the interior and the exterior of the head house were declared New York City Landmarks in 1994, and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.